Architectural Style

Architectural Style

April 1911

May 1911

July 1911

October 1911

February 1912

May 1912

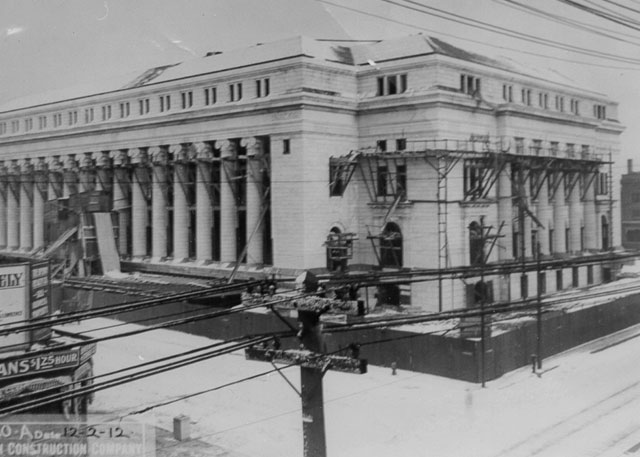

December 1912

August 1914

Although not the first neo-classical building in Denver, its design introduced and popularized this style on a grand scale. Original plans specified the use of Georgia marble, but through the efforts of local businessmen, the native stone “Colorado Yule marble from Marble, Colorado, was used to clad the exterior of the post office courthouse. The Lincoln Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknowns in Washington, D.C. have also been clad with marble from this quarry. The interior facades of the courtyards are limestone, possibly coming from Indiana. This building has been described as “a poem in marble”.

Through the years, as the federal government grew and its agencies expanded, contracted, and changed their missions. By 1964, upon completion of the Byron Rogers Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, the building came to be mostly occupied by the U.S. Postal Service and the U.S. District Court and the U.S Court of Appeals. By 1990, as the judiciary’s caseloads expanded, its courts required larger facilities, the Court of Appeals requested that the Congress approve and appropriate funds sufficient to renovate the Denver Post Office Courthouse. The General Services Administration was called upon to renovate this building. The purpose of the renovation, completed in 1994, was twofold: To convert the entire building to judiciary functions, primarily for the Court of Appeals to accommodate four courtrooms and to the greatest extent possible conserve and restore the historic building in accordance with its status as a Colorado Landmark building, listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Beyond the basic historic restoration, renovation, and conversion issues, this project endeavored to incorporate and upgrade the building’s elevators, heating and cooling, electrical, plumbing, and security to the most current federal functional, life safety, and accessibility standards. The total cost of the restoration, renovation, and conversion was approximately $30 million dollars. This included the incorporation of unique artwork, valued at $120,000, which was guided by the Art and Architecture program of the General Services Administration. The historic building, placed within a contemporary replication context, has been estimated to be valued in excess of $200 million. As with many historical properties the initial and continuing efforts to preserve and conserve an irreplaceable historic structure realistically push the value into the priceless category.

Exterior of the Byron White Courthouse Credit: Wally Gobetz, licensed under Creative Commons

Historic buildings are not always measured by their architectural styles, decorative shapes, and materials, but also by incorporations into their architecture of the less obvious and unique: philosophical inscriptions, names of revered individuals, sculptures, and statuary used to decorate these classical structures. These are historical reminders of what was and may continue to be important. The cities incised in the marble on Stout Street’s entablature above the sixteen columns are a characteristic example: Those cities on the east of the façade are to the east of Denver and those on the west are cities to the west of Denver. These indicated the direction of mail movements to and from the City of Denver. Additionally, incised on the walls bordering these columns are the names of prior Postmasters General. The names on four interior walls of the first floor are of the most well-known of the Pony Express riders. The two emblematic bighorn sheep of the Rocky Mountains, anchoring the 18th Street entrance, are of Indiana buff limestone. These were completed in 1936 by Gladys Caldwell Fisher, a Denver sculptor, as a commission by the Treasury Department’s Public Works of Art Project.

Credit: Jimmy Emerson, licensed under Creative Commons